The Lonely Profession with Orlando Reade

An interview series in which I speak to writers I admire about their work.

Writing is often thought of as a lonely profession. The classic writerly image is of someone chained to their desk, hunched over, all alone. But I’ve also experienced writing as a kind of communion. Communion with other readers and writers whose words and lives have often made mine feel possible. I was told not too long ago that writers never really begin on a blank page, we are simply adding more pages to a text that began before us and will continue after us. ‘The Lonely Profession’- an interview series- was set up to document this fact.

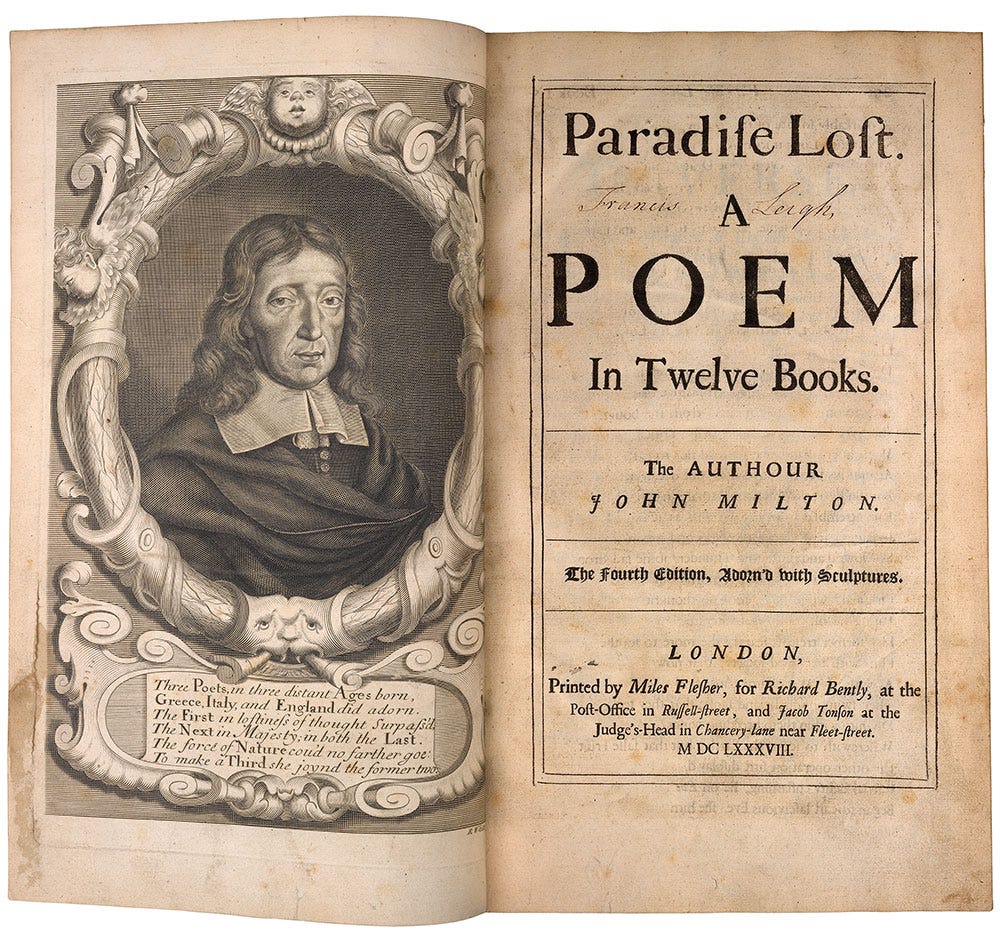

It is fitting to begin ‘The Lonely Profession’ by interviewing Orlando Reade, the author of What in Me is Dark: The Revolutionary Afterlife of Paradise Lost. In one sense, his work is about John Milton’s epic poem Paradise Lost, which narrates the biblical story of the fall of man, the temptation of Adam and Eve by the fallen angel Satan and their eventual expulsion from the Garden of Eden. But more than that, it is a study of literary immortality, taking in both the scandalous life of Milton himself and the revolutionary lives that were influenced by the poem, including Malcolm X, Thomas Jefferson, George Eliot, and Hannah Arendt. By tracing the unruly encounters between Milton and his readers, we are left with a sense of literature’s transformative power.

I read What in Me is Dark toward the end of last year, and I couldn’t stop thinking about it. I was blown away by the precision, dexterity, and beauty of Orlando’s writing, and it was invigorating to reconsider Milton’s classic, which I first read and fell in love with in high school. What in Me is Dark reaffirmed my faith in literature, reminding me of why and how it matters. My hope is that Orlando’s work continues to find and inspire many more readers, just as Milton’s has.

Read our conversation below for his thoughts on London, the canon, dreams, and bad writing advice.

Gazelle: I read that you grew up in London, which I’ve always felt to be a very ‘literary’ city- one of those places that exists as much in books and the mind as it does in reality. How has the city shaped you as a writer, if at all?

Orlando: The truth about where I grew up is a bit more complicated. My family moved around a lot—especially after my parents divorced. It wasn’t until I was 16 that I came to London. By then, I had built it up in my imagination.

London feels like home now, but in a way, that’s specific to someone who arrived later rather than having grown up here from the start. It doesn’t carry the same claim as it does for those who spent their entire childhood here, but I’ve loved London more than anywhere else since the day I arrived.

One of the things I love most about the city is how it feels like a vast memory palace. One of the strange privileges of studying the history of literature is that you come to understand street names in ways that even the people who live on them might not.

There’s so much I could say about London, but that’s the brief version.

Gazelle: Yeah, names like Grub Street- very strange and also very literary. I wanted to know when the idea for the book came to you, what was its genesis?

Orlando: In my book, I talk a little about this. To some extent, the story one gives of a book’s origins is always—if not artificial—at least somewhat arbitrarily selected. You pick a few key moments that led you to write it.

Initially, my relationship with Milton’s work was one of disavowal. I thought, No, I don’t like this. I’m not going to be someone who spends their time thinking about this. But as Freud teaches us, disavowal is often the expression of a deeper, more primary attachment—one that can’t yet be acknowledged. That was true in my case. Eventually, I had to accept that I was going to devote myself to this, to be associated with Milton’s work in a way I hadn’t expected.

About five years ago, I had a dream—grandiose, perhaps, but dreams often are—where I was told, or told myself, that I was going to render Milton’s poetry into modern language. At the time, I thought I would write a play about Paradise Lost and its creation in the wake of the English Civil War, which is a dramatic story in itself. But in the end, that idea evolved into my book. From that point on, writing about Milton felt like something inevitable—like fate.

Gazelle: I like that the book began with a dream, I think Milton would appreciate that. But how did you make that dream a reality? Paradise Lost is referred to as one of the most influential poems in the English language. How do you step up to the challenge of writing about a text that has a phenomenal amount of criticism and critical responses?

Orlando: Being able to write about a subject that was both vast and extensively explored by other writers meant accepting that my work would be, at best, partial and, at worst, irresponsible. Since the book came out, I’ve occasionally realized there were scholars I should have cited or books I should have read. I did read a lot—but not everything—and I didn’t let that worry me.

At some point, I made a more or less conscious decision that it was worth writing a book on a big subject, even if I couldn’t cover it with absolute scholarly completeness, rather than choosing a smaller subject I could handle with full academic rigor.

Gazelle: I’m interested in how you bridged the world of scholarly writing and trade non-fiction? What was it like navigating those two very distinct ways of writing about literary texts?

Orlando: I never set out to be an academic—I always wanted to be a writer. I decided to do a PhD mainly because I wanted more time to have life experiences and learn things that would be useful to me as a writer. But at some point during my PhD, I had to fully commit, which meant letting go of other kinds of writing. I experienced that as a kind of loss, but it was necessary to fully inhabit the demands of the PhD. It was an unhappy experience.

When I finished and was out in the world—where no one really cared what I was working on—I ended up finding a middle ground. I was writing a non-academic book about a subject I had been trained to think about responsibly. Ironically, it was only then that academics started taking an interest in what I was doing.

At the time, I thought writing a book about Paradise Lost would be met with disdain, but to my surprise, other scholars have been very welcoming. That said, I’m happier considering myself just a writer rather than an expert or a scholar. In my book, a scholar is someone who can read Latin—and my Latin is quite rusty.

Gazelle: So when did you first realize you wanted to be a writer?

Orlando: That’s a good question—I can’t really remember. But I think it happened early, probably around 12 or 13, in that hyper-awkward phase of heading into your teenage years, where everyone is figuring out what they’re good at. One of my friends played guitar, someone else was good at skateboarding—I wasn’t good at either of those things. But I realized that what I was good at was writing. And from that point on, it’s been my only real professional goal.

Gazelle: Whenever I think of criticism and the canon, I tend to think of belonging. My time as an undergraduate was shaped by a reckoning with the canon—who it was for and who it served. Those questions feel very much at the heart of What in Me Is Dark, and I was wondering about your thoughts on that.

Orlando: Yeah, I have a lot of thoughts about that. I think my book engages with that question in two ways. The first—and the one I feel slightly less comfortable with—is the concern that, in looking at how different writers have responded to Milton, I might be instrumentalizing their identities or experiences to argue for Milton’s continued relevance. That could seem like a conservative project, and I want to acknowledge that impulse because I don’t think it’s entirely absent from my thinking.

But more importantly, what I care about is the idea that artworks are inhabited by their readers—the people and communities who make sense of them. No one truly owns great works of literature; they are radically democratic, like public land, a space where anyone is free to dwell and encounter others. That’s the version of Paradise Lost I wanted to champion because, while it’s one of the most famous texts we have, it also carries an aura of exclusivity. It can seem like it primarily invites belonging for people like me—those who share certain aspects of Milton’s identity. But the truth is, it’s far more expansive and interesting than that.

It was a joy to follow the different paths the poem has traveled and, as you saw in the book, to end up telling more of the story of its readers and what was happening to them than discussing Paradise Lost itself. In some ways, my book is only pretending to be about Paradise Lost.

Gazelle: I love the title What In Me Is Dark, and it made me think about how people often say that the purpose of studying history or reading literature is to illuminate our understanding of the human condition—as if knowledge is something that brings light, clarity, and revelation. But your approach seems to go in the opposite direction, focusing more on darkness in writing, in a way that resists the metaphor of illumination. I was wondering if you could talk about that a bit.

Orlando: There's such a long history of thinking about light and shadow in ways that resist the classical Greek metaphor—at least the one we inherit from Plato, where light represents truth and knowledge. Many writers have pushed back against that over the years, and Milton is one of them. His paradoxical descriptions of hell in Paradise Lost—particularly "darkness visible"—invite us to see darkness as far richer and more complex than our usual metaphors about light and shadow suggest.

Milton had a distinctly Baroque fascination with darkness, much like Caravaggio and those dramatic, gruesome Italian biblical painters. That obsession is part of what makes Paradise Lost such a compelling and layered poem. He wasn’t just justifying ‘the ways of God to men,’ as he claimed—he was also crafting something deeply literary, ambiguous, and resonant. And that complexity is what has allowed so many later readers to find their own meanings in the text.

artworks are inhabited by their readers—the people and communities who make sense of them.

Gazelle: I admire how your writing is never simply analytic, but also visual and descriptive. This might sound cheesy- but it made history ‘come alive.’ I keep thinking about how you had this ability to move seamlessly across centuries and completely different contexts. It seemed so effortless but I imagine took a great deal of work. Could you talk a bit more about writing history as a nonfiction writer—how you approach it without the pleasures of invention that fiction writers enjoy?

Orlando: For me, it’s always about how to do justice to more of the world as it actually exists.

A few years ago, I met the writer Katherine Rundell briefly at a party while she was working on Super-Infinite, her book about John Donne. She mentioned that she had just switched publishers—her former American publisher had wanted her to do more of what we might call speculative nonfiction. She gave an example: they wanted her to write something like John Donne sat at a window, looking out at the snow outside. At the time, I had just started writing my own book, and I found that such a useful thing to think about.

I asked myself: Am I going to allow myself to speculate about things that could have happened? Or am I going to stick to the facts? Of course, speculation has its advantages—it makes writing more cinematic, more immersive. But I realized over time that I couldn’t allow myself to do that, or if I did, I had to clearly mark it, grammatically—phrases like we might imagine that Malcolm X’s expression was this were as far as I was willing to go.

Instead, I started looking for moments I could dramatize using only the facts I had. I guess I landed somewhere in the middle. For instance, I found a letter at the Schomburg Institute archives in Harlem where Malcolm X actually describes looking out of a window. I used that moment in my book, partly as a joke to myself—proof that if you do the work, if you find the facts, you can have your cake and eat it too. You can create drama without needing to invent.

Gazelle: Yeah, that’s funny, and it actually leads nicely into my next question—did you have any other tricks or jokes while writing? Because I feel like Milton was definitely someone who left a lot of coded jokes and messages for his readers, right?

Orlando: That’s a good question. There weren’t any covert messages, but I do think non-fiction—especially biography—allows you to explore parts of yourself without being confessional. It’s not autofiction; it’s more about a principle of identification.

For example, when writing about Virginia Woolf, I found myself navigating a complex relationship with her work—particularly Orlando—which, in turn, made her feel more alive to me. I allowed myself to dwell in the areas where I identified with her, where I disliked her, and where I admired her, without needing to make those feelings explicit.

At one point, I thought the book might end up being more about me—not because I wanted it to be, but because I assumed that’s what a publisher would expect. It was a relief to find out they didn’t need that much of me in there, which allowed the subject itself, or rather the subjects, to take center stage.

Gazelle: What do you think people so far might have gotten wrong about the book?

Orlando: The most frustrating misreading of the book also happened to be the most high-profile one—Merve Emre’s review in The New Yorker. At one point, she wrote something like, “Reade seems to sympathize with Satan,” which was definitely not on my 2024 bingo card—being accused of sympathizing with Satan by The New Yorker—but I’ll take it.

Of course, being misread is part of the project itself. Still, I can’t help but feel that if she had read the whole book carefully, she would have reached chapter 11 or 12, where I state very clearly that Milton wanted to tempt us into sympathizing with Satan—only to show us, by the end of the poem, why we shouldn’t. So it was frustrating that she either didn’t read that far or didn’t engage with that argument.

She also suggested that Malcolm X’s reading of Paradise Lost might simply be considered a misreading. In one sense, that was useful—she was articulating a perspective that many Milton scholars hold. But that’s exactly what I was arguing against in my book: the idea that we need to police who is reading Milton “correctly” rather than celebrating the variety of interpretations, while still engaging with the question of what is right and wrong. That was the part of the review I found most disappointing.

Gazelle: What’s the worst bit of writing advice you’ve ever received?

Orlando: I think my relationship to writing advice has become quite catholic—I take it all in. For a long time, I was resistant to books about writing, those instructional guides, but in recent years, I’ve adopted more of a give me everything approach. I’ll read Stephen King’s On Writing or Patricia Highsmith’s book on suspense fiction just to see what sticks. The more, the merrier.

If writing advice is bad, I tend to forget it. But anything that encourages me to write feels positive. What’s far more painful—and what actually makes writing difficult—are the offhand comments people make in conversation that subtly undermine the process. People can be so casually dismissive when they ask what you’re working on. I remember someone saying, “Oh, that sounds very academic.” That kind of offhand remark can be the most disabling feedback.

At one point, I thought the book might end up being more about me—not because I wanted it to be, but because I assumed that’s what a publisher would expect. It was a relief to find out they didn’t need that much of me in there, which allowed the subject itself, or rather the subjects, to take center stage.

Gazelle: If you weren’t a writer what would you be doing?

Orlando: In recent years, I seriously considered becoming a psychotherapist as an alternative path. It felt like a natural extension of some of the skills I had developed as a teacher—listening, encouraging self-expression, helping people articulate their thoughts. Ultimately, I decided not to pursue it, partly because I needed to finish my book. By the time I did, I realized that writing was my primary focus.

That said, I love the creativity of therapy. Years ago, before experiencing therapy myself, I naïvely thought it might be an obstacle to creativity. But going through it made me realize how generative it actually is—how powerful it can be to give people the space to voice things they’ve never been able to say before.

Gazelle: Last question, any book, movies or music you’d recommend to readers?

Orlando: Yes- Phyllis Rose, Parallel Lives: Five Victorian Marriages, Emergency Ward: Nina Simone in Concert and 35 Shots of Rhum, dir. Claire Denis.

thank you for running this substack. I enjoyed learning from this interview.

I loved every bit of it and I’ll be back here to read / listen again. It’s refreshing and I hope you do more of this